Researchers at the University of Chichester have used eye-tracking technology to highlight the complex strategies developed by musicians while learning musical scores.

The new study by Professor Laura Ritchie and Dr Benjamin T Sharpe, titled ‘Gaze Behaviour of a Cellist: From Sight-Reading to Performance’, explores how an expert musician learns a new piece of music. It revealed that the score moved from being used as detailed instructions to become navigational anchors for the musician.

The research, due to be published in Musicae Scientiae, captured information from the initial sight-reading of the score to a performance run-through.

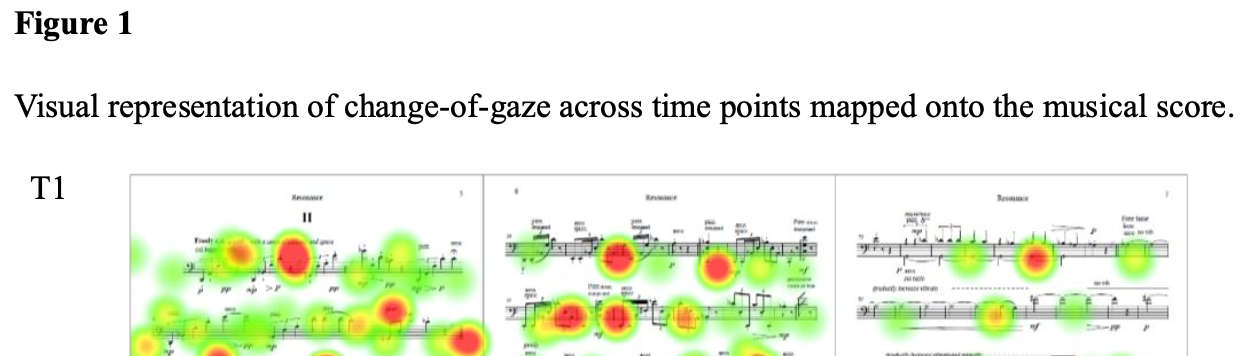

It found that although the musician’s eyes initially moved systematically across every note, fixating evenly throughout the score, by the final session the gaze had shifted dramatically, concentrating on the beginning of each musical line.

The subject of investigation was the second movement (‘Introspection’) of Resonance, a newly composed piece of contemporary classical music for the cello by Jill Jarman.

Unlike previous research relying on self-report and observation, this study combined analyses of physiological data and the musician's reported thought processes, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the learning-to-performance journey.

Dr Benjamin T Sharpe, Senior Lecturer in Cognitive Psychology at the University of Chichester, said: “As an exploratory single-case study, the findings are tentative but reveal intriguing patterns that challenge assumptions about musical learning. Early sessions showed intense visual attention on complex fingerings and bow techniques, with verbal commentary about 'problem-solving' challenging passages. Later sessions revealed sustained fixations on sections requiring interpretative nuance, long sustained notes demanding expressive control rather than technical precision. By the final session, the musician’s gaze had shifted dramatically, concentrating almost exclusively at the beginning of each musical line, using the score as cognitive navigational anchors rather than detailed roadmaps.

“The pupillometry data showed peak cognitive effort shifting from structural challenges to expressive demands as learning progressed, tentatively aligning with established theories about expert learning: structure first, technique second, expression last.”

Laura Ritchie, Professor of Learning and Teaching at the university, said: “I am very pleased to contribute this unique, longitudinal eye-tracking study to the music learning literature. This study presents a unique look into the learning process, and it was fascinating how the eye-tracking data told the story of both focused effort and attention, which was very different to how it was perceived as the performer. From behind the music stand there are associations of what makes something ‘hard’. This research challenged those, making me aware of unseen biases about learning and reading. This research has the potential to open the door to our understanding of how we focus effort and cognition to learn music and musicality”.

During the study, a combination of frame-by-frame and automated analysis of eye-tracking data allowed the capture of significant amounts of information across three data-collection points. Patterns of learning relating to technical challenges were displayed by data gathered from the cellist’s eyes across the recorded sessions. Initial links between self-reported thinking, cognitive processing, and the resulting recorded performance sessions were explored in the research. Results provided preliminary insights into connections between perception, cognition, and performance, and advanced-level music learning approaches and performance practices.

Eye-tracking technology reveals where the musician's gaze rests when reading a score. Credit: University of Chichester

Dr Benjamin Sharpe added: “While these preliminary findings suggest implications for music education, larger-scale studies are needed to confirm these patterns. This exploratory work opens possibilities for understanding musical expertise through visual attention, potentially informing future research on pedagogical approaches and performance preparation strategies.”

Chichester District is open for business

Chichester District is open for business

£8.6 million approved to support the development of Homefield Primary School in Worthing.

£8.6 million approved to support the development of Homefield Primary School in Worthing.

South hit by lightning strikes and flooding as storm sweeps region

South hit by lightning strikes and flooding as storm sweeps region

New plans for redevelopment of former Gosden Green Nursery site in Southbourne.

New plans for redevelopment of former Gosden Green Nursery site in Southbourne.

Remembering Lord Tebbit and the IRA bomb attack in Brighton

Remembering Lord Tebbit and the IRA bomb attack in Brighton

Deadline approaching for West Sussex residents to share views on future of local government

Deadline approaching for West Sussex residents to share views on future of local government

Witnesses sought for A27 collision involving two HGV's

Witnesses sought for A27 collision involving two HGV's

Man remanded in custody charged with Chichester stabbing

Man remanded in custody charged with Chichester stabbing

UPDATED: 31/07/2025 @ 15:24 - South braces for thunderstorms

UPDATED: 31/07/2025 @ 15:24 - South braces for thunderstorms

Delayed decision over Local Plan in Horsham

Delayed decision over Local Plan in Horsham